Background

Lu Zhan Qi (陸戰棋) (aka Army Chess, or War Chess) is an uncommon 2.5 player strategy game that I was first introduced to in high school. Unlike regular chess, this game relies on imperfect information as players do not know the identity of their opponent’s pieces. Therefore, an impartial “referee player” is needed (hence the 0.5 player requirement) to determine the outcome of a battle, without revealing the identity of the players’ pieces to each other [1].

While I loved this game growing up, it was often very hard to play with my friends because it was nigh impossible to find a referee. It was essentially trying to find someone to be an active spectator, or constantly interrupting whatever activity they were doing at the time.

Fast forward many years, when I stumbled upon my copy of Lu Zhan Qi in the attic. After my initial excitement to play it again, I realized I still had the same problem: I didn’t have a referee to play with. While online versions probably exist, I spend much of my time online already, and enjoy opportunities where I can disconnect and play a board game in real life.

Then, I had a spark of inspiration: what if I built a raspberry PI referee? Its task would be simple – be shown two images, and determine which player would win in the battle. No longer would I have to convince other people to watch me play games, and it would still preserve the unique imperfect information component that this game creates.

After all, how hard could it be?

Objective

Build a system that would process video input and identify the chess pieces that it was shown. Then, have it display which player won, without revealing the identity of those pieces.

Solution

Before I dive into the details of my approach, I want to preface with the fact that I have no prior experience with the field of computer vision what-so-ever. My core assumption during this project was that I would not be forging any new ground, rather, hooking up existing systems together for my own personal entertainment. I am confident that all trained models that I would need already exist – just not combined in the way they are for this exercise.

Constructing a Minimum Viable Product (MVP)

I am a huge proponent of iteration, and this often comes hand-in-hand with creating an MVP. What’s the simplest thing you can create to test whether your idea is viable?

After several hours of research and jumping down several rabbit holes of computer vision related topics, I decided on the following design choices:

1. Use OpenCV to interact with the inbuilt webcam.

There wouldn’t be any point buying parts for a raspberry PI, if the initial idea flops.

2. Requiring manual user input to capture images, rather than leveraging an object detection algorithm.

It turns out object detection is a pretty hard problem! I was really optimistic with the EAST text detection model, but then I quickly realized that it was trained on English words and could not meet my needs. Therefore, I had to rely on human intervention to position the piece in a way that the computer would be able to recognize.

3. Capturing sequential actions, rather than simultaneous actions.

Initially, I conceptualized that this computer referee would be displayed two pieces simultaneously, and then be able to determine which piece won. However, as a result of #2, we needed to move to a sequential flow to support the limitation that the computer could only process one image at a time.

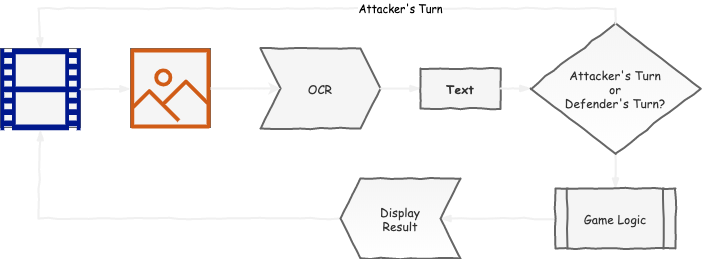

As a result, this is the final system diagram I arrived at:

The final code can be found on https://github.com/domanchi/war-chess-referee.

Issues Encountered

No technical blog post would be complete without describing some of the issues encountered. And there were many – I mean, this was the first time I was experimenting with computer vision tooling.

OpenCV did not play well on Windows Machines

Generally speaking, Windows Subsystem for Linux (WSL) is pretty good. It’s almost like Linux for many aspects, except for the rare edge cases when it’s extremely obvious that it is not Linux. This was one of them.

Shortly after setting up my dev environment to explore OpenCV’s capabilities, I realized that I could not use a Windows machine to continue developing this project. This was a great reminder to always run a “Hello World” example before going too deep, otherwise, you may encounter show-stopping issues later down the road.

The EAST model was trained on English text only

The Efficient and Accurate Scene Text (EAST) detection pipeline is actually really cool. I managed to hook up a system to recognize English text, and configured it to support higher rotational angles with decent performance and accuracy. However, I got a bit too excited with it, and did not test with Chinese text earlier on. So after I tested it with actual game pieces and realized it was a dead end, I had to pivot and redesign my MVP.

Tesseract wasn’t working out of the box

Tesseract is often the go-to OCR solution that unfortunately, did not work for me. After installing the required chinese models (and testing on actual game pieces), it was unable to output the text that I was expecting.

This started a journey in finding another Chinese language OCR system that did not require an online connection (constantly sending images to a cloud service to process? Uhh, no thanks). I eventually realized that I had to tweak my search queries to look for sites that were primarily in Chinese, to look for a Chinese OCR system. Fueled by determination and Google’s translate service, I stumbled upon https://github.com/ouyanghuiyu/chineseocr_lite which played a crucial component in designing my final system.

Thank goodness this was on Github. I may not be able to read Chinese, but I sure can read and reverse engineer code.

The OCR Engine was unable to obtain 100% accuracy

In testing, I quickly realized that while the OCR engine was pretty good, it wasn’t perfect. For example, it had trouble identifying the second character of 地雷 (land mine), thinking it was 香, 冒, 面, 蕾, 宿, 蛋 and 置 (among other candidates). However, thankfully it was able to decipher the first character with relative ease.

I addressed this issue by being flexible with the game logic, preferring to identify the first character first, then using the second character if absolutely necessary. This turned out surprisingly well.

Future Improvements

Removing the Manual Intervention Step

It’s really annoying to position the piece over the webcam, then press the spacebar to capture the image. It would be a big win if I was able to remove the need to press the spacebar, and have the system automatically identify that a piece was ready for OCR processing.

Several ideas that could help accomplish this:

-

If I found a trained EAST model on Chinese text, it would be able to detect text in natural scenes. This way, the video could constantly stream, and the system could extract images based on identified bounding boxes from the model. I reckon this model already exists, however, it’s just a matter of whether this pre-trained model exists in the public domain.

-

We could also take an object classification approach. Since there’s only a limited number of pieces to identify, we could train the model to specifically recognize these pieces as individual, unique items (rather than tiles to be translated). This has the potential to skip the OCR step altogether – however, I can’t comment on the efficacy of this approach as the model may merely recognize the fact that it is a piece, rather than the identity of the piece itself.

-

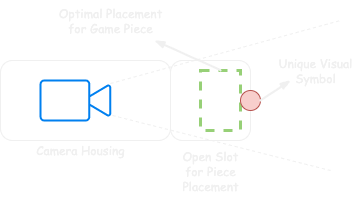

Finally, there is a hardware alternative. Since it’s already difficult to know where to place the piece over the webcam (to get the right position / distance from the camera), one can imagine building a contraption that made it easy for humans to know where to put the piece for recognition. This way, we can train the model so that when it doesn’t see the “unique visual symbol” (e.g. line of sight blocked by a piece), it would start capturing images to process via OCR.

Moving to a Raspberry PI

This would really improve the usability of the system (as depicted in the hardware alternative above), but may potentially encounter performance issues. Currently, I’m using an 2.3 GHz Dual-Core Intel i5 (no GPU support) to power this system and it seems fine, but who knows when moving to a raspbian-based hardware. Furthermore, there are probably hardware compatibility concerns that I would also have to address.

If you want to try addressing some of these potential improvements, feel free to fork my repository and work off my initial starting point!

Summary

This project took me about a day to investigate, build and blog about. It has been a fascinating foray into a subset of the current state of computer vision, and learning about the possibilities and limitations of building systems on consumer-grade hardware. I loved that I could get started relatively quickly without training my own models (which I’m told is the longest part), and more importantly, achieve my initial objective to build an unbiased computer referee that enabled me to play this game with only two players.